I was there to present my own paper on Young Adult fiction, looking at the LGBTQ representation in Young Adult fiction and focusing on a couple of books in particular to chart the changes over the decades - beginning with Annie on my Mind by Nancy Garden and concluding with The Miseducation of Cameron Post by Emily Danforth and Keeping You a Secret by Julie Anne Peters. I framed the discussion in the context of the quote from David Levithan's Two Boys Kissing: "...just because it's better now, doesn't mean that it's always good" and I have since been pondering on my own paper and general discussions with other attendees which I wanted to touch upon in this post.

There's an interesting debate in the context of LGBTQ literature, where many who write, read and study YA fiction suggest that what we need is less of the formulaic 'issues' based books, and more actual stories featuring queer protagonists in leading roles where being LGBTQ just is, instead of being the core focus or issue at the heart of the story. There seems to be a general resistance at times about the value of issues based YA which can be seen as didactic, formulaic, derivative and - at times - patronising. Fair point. Young adults don’t want to be told how to deal with something so core to individual identity by an adult writer who can't understand their specific experience due to being of a ‘different time’ or, in some cases, coming from a position of privilege or different cultural experience which might fail to resonate with the reader. Fiction is not the right place for instruction. Instruction manuals are the right place for that. Fiction should be free and uninhibited, rather than aiming to educate a generation. The very act of reading allows the reader to immerse themselves in another world and see life through the eyes of other characters. There’s an element of glorious escapism to discovering new worlds and characters. A reader can easily be thrown out of a story which reads as if it’s trying to preach, teach or convert. If the author writes with the sole purpose of didactics they run the risk of neglecting the fact that the best fiction contains, when everything else is stripped away, a damn good character – a damn good story – the best kind of book knocks the air out of your lungs and leaves you mulling it over for days. It has its readers captivated by its characters or sitting up well beyond bedtime, turning the pages to discover how the story ends. Of course fiction can be political, angry, subversive and hold a mirror up to society and show it an unhappy reflection – ultimately, however, it needs to be well-written and engaging enough to keep the reader interested in the characters and the stories beyond the politics.

For these reasons, I’m certainly not advocating we need another raft of coming out stories which very consciously seek to assist LGBTQ teens with coming out to parents, friends, at school and so on. I do not advocate for more queer issues based YA literature because of its didactic properties. I also wholeheartedly agree that the increased number of LGBTQ characters in YA fiction is a vital and important shift in the right direction. LGBTQ children and teens need to see themselves represented not only in but as the next Harry Potter, Katniss or whoever the hero or heroine of the time might be. As children’s literature increasingly crosses boundaries in terms of the reading demographic with more adults than ever turning to children’s and YA fiction as teens read widely in the adult market, that shifting trend is as important for today’s adults and yesterday’s teens as it is for the target reader of the YA market. A lot of contemporary discourse around modern LGBTQ activism is around the fact that we are increasingly entering a brave new world where individual sexuality and gender identity will simply be what it is, as opposed to being an issue which requires individuals to come out and to identify themselves as something different or something other. Increased visibility in stories which don’t turn on the issues of sexuality or gender are vital in normalizing the LGBTQ experience and offering visibility to LGBTQ teens and straight, cis-gendered teens alike, which make the LGBTQ contemporary teen feel less marginalized as a result of their sexuality or gender identity.

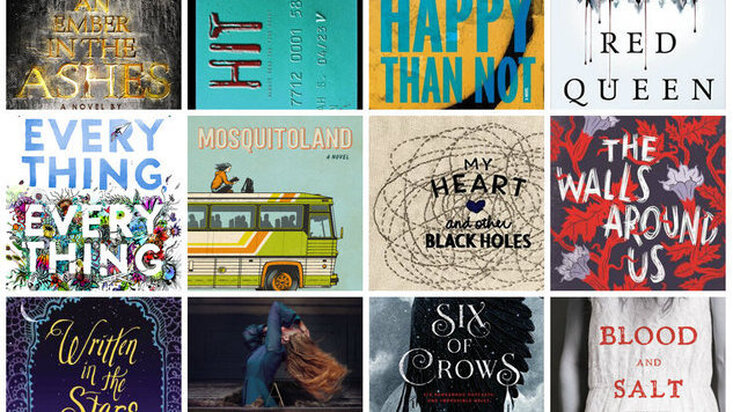

I would advocate that the YA market develop more stories with LGBTQ characters together with continuing to write about the struggles that might be faced by today’s LGBTQ teen. I still firmly believe LGBTQ ‘issues’ stories still have a very important place in the YA market precisely because – in the words of Levithan’s omniscient narrator in Two Boys Kissing – although things might be better, that doesn’t mean they are always good. In 2014, 19 year old Daniel Pierce came out to his father, step-mother and grandparents and filmed the interaction with his family which was abusive and violent. Daniel is not alone in his story, the overwhelming response to his video when it posted online is representative of that. There have been countless other stories of teens being beaten or disowned because of their gender or sexuality and there are still all those whose stories we might not hear because people are too scared to speak up. There are problems specific to faith communities which the theme of this year’s LGBT History Month went some way to address, and there is still the innate fear of some teenagers of being something different – something ‘other’. While the Vloggers of today who speak openly about sexuality and gender and the broader internet based communities offer safe spaces (depending on the sites) to today’s LGBTQ teens, there are those teenagers who find their Narnia in words and books. To write stories only in a world where people are completely free to be who they are would ignore the still significant number of people who still face struggles as a result of their sexuality or gender, those who might find something in YA fiction which is so like their own experience – their own story – it provides salvation, of a sort. Whilst I may not be advocating that we bring back the didactic, instructive form of YA fiction, I’m hopeful that the trend in the YA market towards confronting issues which face teenagers of the moment doesn’t shift away from addressing the struggles of some LGBTQ teens in an era of much positive progress and heightened visibility for the LGBTQ community. Contemporary issues stories are much more nuanced and well-written than their predecessors and I am personally very happy to books like Lisa Williamson’s The Art of Being Normal, Silvera’s More Happy Than Not and Gregario’s None of the Above dominating the YA market in 2015.

I would also welcome YA stories which offer some insight into the struggles of LGBTQ community of generations past. Just as I maintain it’s important that the next generation is equipped with knowledge which will enable them to try to be an educated and collective voice resisting history repeating itself, I would argue there’s an important political backdrop to the LGBTQ movement which needs to be disseminated widely to future generations by those who were there. There’s a history which can – if shared by today’s YA authors – instill a better understanding in today’s teen reader and perhaps offer hope for a brighter future in their own struggles. Levithan’s Two Boys Kissing is a text which does this wonderfully with the omniscient narrator – the gay men of the AIDS generation – who watch the queer teens of Two Boys negotiate growing up, sexuality, love, romance, sex and gender identity and observe how the tide has changed for the LGBTQ teens and how welcome those freedoms are. There is never the sense that Two Boys Kissing falls into the didactic ‘educational’ issues book which attempts to tell teenagers how they should deal with a particular issue with which they find themselves confronted or which simply educates in a bland an dispassionate manner. Instead it is a gorgeously told, poetic narrative which is real, honest and bittersweet. It does something important in that it gives a voice to those lost in the eighties and allows them to communicate to the teens of today. In that sense it is an important book but it is more than that – it’s a confident, poetic story told in glorious prose which the reader can enjoy simply because the writing is so bloody good. It’s a book everybody should read, not because of its political merits but because it’s a fine piece of literature. It’s the kind of book that makes people who claim YA literature is somehow substandard writing sit up and take notice.

We may be coming into an era where coming out is not a big deal but I don’t think we’re fully there yet. There’s still a real lack of visibility around grey and non-binary sexuality, there’s a lot of work to be done in respect of helping trans* people get the sort of legislative protective measures to which they are entitled and to educate people on gender non-binary identities. The well-represented coming out stories still matter because they are still real. They are still happening. It would be great to see more cultural diversity in those stories but in all their forms, they need to continue to be told. They might not offer a happy ending or a neat resolution, but even where they do not, they can give a taste of freedom for today’s teens. This juxtaposition of overt homophobia with the sense of pride and liberation in coming into one’s own identity is neatly captured by Julie Anne Peters in her fantastic 2004 YA novel, Keeping You a Secret: “The best thing about coming out is, it's totally liberating. You feel like you've made this incredible discovery about yourself and you want to share it and be open and honest and not spend all your time wondering how is this person going to react, or should I be careful around this person, or what will the neighbors say? And it's more. It's about getting past the question of what's wrong with me, to knowing there's nothing wrong, that you were born this way. You're a normal person and a beautiful person and you should be proud of who you are. You deserve to live with dignity and show people your pride.” I would argue that, just as today’s young girls need feminism as much as they ever did, LGBTQ teens of today continue to need YA literature which explores the whole gamut of LGBTQ experience.