Taylor Swift Photo Credit: Beth Garrabrant

As the world grew quiet and countries imposed localised or national quarantines and shut down large public gatherings, music has been in a state of flux with new releases postponed, concerts cancelled and many artists describing a sense of creative malaise. For music fans, that joy of liveness became a site of palpable longing. The sweat and thrum of bodies in a pub or concert hall turned into an impossible dream and the sunshine and freshly cut grass served as a reminder of cancelled festivals and the absence of friends. Missing live music is something Rob Sheffield wrote about in a piece called Life Without Live featured in Rolling Stone magazine and I won’t repeat those sentiments here. Instead, I want to reflect on just a small sample of the music that has been produced during lockdown and the way musicians and music fans have adapted to life in lockdown.

|

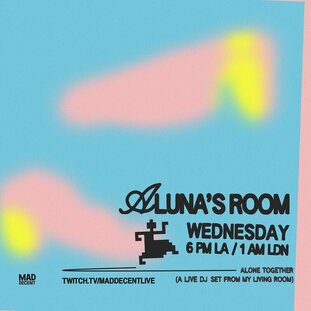

As with many sectors, those involved with the creation and production of music have had to think quickly and creatively about ways to stay connected during quarantine. Many have rallied together and harnessed digital platforms to livestream and collaborate, bringing live performance to our computer screens and homes. Diplo’s Los Angeles based record label Mad Decent has been livestreaming daily on Twitch, featuring artists such as Aluna in Alone Together sets live from the living room. Lady Gaga teamed up with the World Health Organization and Global Citizen to raise funds for COVID-19 protection worldwide through the Global Citizen’s One World: Together At Home concert. The number of acts livestreaming has been substantial and Billboard has produced a comprehensive list here.

|

The Internet has provided artists with the ability to stream their music in real time, fostering that sense of liveness in a world where large gatherings haven't been possible. Certain genres of music have perhaps been better suited to social distancing, the challenge greater for bands and groups or for those with limited resources in their own homes than for solo DJs and other solo artists with the right tech to hand. In those cases, certain artists, particularly those already used to operating through livestreaming, have been better able to adapt to music production, creation and dissemination during quarantine. However, the fact producing and sharing music during lockdown may have been easier for some artists or certain platforms than others, is not to negate the challenges faced by everyone in the music industry. Even mediums that are specifically designed to deliver music to our homes, such as the radio, have had to make rapid changes during the pandemic. In the UK for example, many regional stations with less funding have suffered the economic ramifications of COVID-19, while the larger stations such as Radio One have had to adapt to a new way of life, running their annual Big Weekend music festival virtually and quickly rescheduling line-ups, celebrity interviews, production and content creation in a way that enabled the teams working on the regular radio shows to continue to operate in a safe way, in accordance with government guidelines.

In terms of those creating music, the output reflects the way the pandemic drummed up a sense of togetherness and at the same time had a very different and personal impact on individuals. Some artists have spoken about feeling creatively stifled during the pandemic, others have written entire albums during the period. The nature of the music produced during lockdown too has not followed one specific trend. Some artists have responded directly to the pandemic from Gmac Cash’s Coronavirus to Pitbill’s I Believe We Will Win, the latter featuring fan contributions from people dancing in isolation, frontline workers and Zoom video conferencing calls interspersed with images of people wearing masks, holding signs about rising up and responding to the new challenges of the pandemic. This tactic of using fan contributions and splicing them together has been used by many artists during the lockdown, from Pitbull to Oh Wonder’s Keep on Dancing, part of a Home Tapes Video series the band put together. Together with more traditional music output the popularity of platforms such as TikTok have provided the ideal space for humorous, quasi-musical parodies, like Laura Clery’s Quarantine Workout performed as her alter-ego Pamela Pupkin—“we’re sprayin’ and we’re prayin’ / stay inside move side to side.”

Together with the new music released during quarantine, songs released before quarantine have been re-released with new socially distant music videos such as HAIM’s I Know Alone and some artists who had created music videos pre-quarantine released the videos during lockdown, with a reflection on how quickly socialising as we know it has changed. One example is the music video for Watermelon Sugar by Harry Styles, which begins with the date of release and the tongue-in-cheek caption “this video is dedicated to touching.” Some artists have remixed their own works so they speak directly to life in a pandemic, such as Todrick Hall’s Quarantine Queen album, on which he renames his single ‘Nails, Hair, Hips, Heels’ as Mask, Gloves, Soap, Scrubs with humorous nods to the trends of quarantine like sanitising, tidying the house, the obsession with Netflix documentary Tiger King and the boom in video conferencing: “Zoom is the new club.” Several of the songs I've referenced are undoubtedly humorous which might jar in the face of a very serious matter, but in many ways it is precisely this kind of engagement that is the hallmark of Internet culture, a space where satire is preferable to hollow sentimentality and can provide more accessible moments of relief and heighten camaraderie.

Together with one-off singles and remixed works, other artists have released albums of entirely new music penned and recorded largely during the period of isolation. Taylor Swift's Folklore, a dialled back approach to her previous albums, has already gained critical success and at times seems to speak directly to the experiences of quarantine. The opening track ‘the 1’, co-written with The National’s Aaron Dessner, contains the line “I have this dream you're doing cool shit / Having adventures on your own / You meet some woman on the internet and take her home.” Another album, Charli XCX’s How I’m Feeling Now, is a stark contrast to Swift’s pared back, contemplative Folklore, with the electronics and tuning turned up to the max, but it too has received critical acclaim and was shortlisted for the Mercury Prize.

In many respects the albums speak to different moments of lockdown, with Charli XCX’s album released on 15 May 2020 and Swift’s on 27 July 2020. Both feature collaborations, Charli XCX with her fans and Swift with various musicians such as Dessner and Bon Iver. How I’m Feeling Now uses electronics, filters and audio techniques that replicate being quarantined in a digital age, whilst Swift's Folklore is minimalist. In the videos too there’s a marked difference in approach, in the case of Charli XCX, the vibe of the album is best captured in the trippy music video for ‘Claws’, with green screen digital backgrounds and kissing cyborgs that replicate the strangeness of isolation where human contact exists through the interface of our computer screens, connections forged through our Internet bubbles.

In terms of those creating music, the output reflects the way the pandemic drummed up a sense of togetherness and at the same time had a very different and personal impact on individuals. Some artists have spoken about feeling creatively stifled during the pandemic, others have written entire albums during the period. The nature of the music produced during lockdown too has not followed one specific trend. Some artists have responded directly to the pandemic from Gmac Cash’s Coronavirus to Pitbill’s I Believe We Will Win, the latter featuring fan contributions from people dancing in isolation, frontline workers and Zoom video conferencing calls interspersed with images of people wearing masks, holding signs about rising up and responding to the new challenges of the pandemic. This tactic of using fan contributions and splicing them together has been used by many artists during the lockdown, from Pitbull to Oh Wonder’s Keep on Dancing, part of a Home Tapes Video series the band put together. Together with more traditional music output the popularity of platforms such as TikTok have provided the ideal space for humorous, quasi-musical parodies, like Laura Clery’s Quarantine Workout performed as her alter-ego Pamela Pupkin—“we’re sprayin’ and we’re prayin’ / stay inside move side to side.”

Together with the new music released during quarantine, songs released before quarantine have been re-released with new socially distant music videos such as HAIM’s I Know Alone and some artists who had created music videos pre-quarantine released the videos during lockdown, with a reflection on how quickly socialising as we know it has changed. One example is the music video for Watermelon Sugar by Harry Styles, which begins with the date of release and the tongue-in-cheek caption “this video is dedicated to touching.” Some artists have remixed their own works so they speak directly to life in a pandemic, such as Todrick Hall’s Quarantine Queen album, on which he renames his single ‘Nails, Hair, Hips, Heels’ as Mask, Gloves, Soap, Scrubs with humorous nods to the trends of quarantine like sanitising, tidying the house, the obsession with Netflix documentary Tiger King and the boom in video conferencing: “Zoom is the new club.” Several of the songs I've referenced are undoubtedly humorous which might jar in the face of a very serious matter, but in many ways it is precisely this kind of engagement that is the hallmark of Internet culture, a space where satire is preferable to hollow sentimentality and can provide more accessible moments of relief and heighten camaraderie.

Together with one-off singles and remixed works, other artists have released albums of entirely new music penned and recorded largely during the period of isolation. Taylor Swift's Folklore, a dialled back approach to her previous albums, has already gained critical success and at times seems to speak directly to the experiences of quarantine. The opening track ‘the 1’, co-written with The National’s Aaron Dessner, contains the line “I have this dream you're doing cool shit / Having adventures on your own / You meet some woman on the internet and take her home.” Another album, Charli XCX’s How I’m Feeling Now, is a stark contrast to Swift’s pared back, contemplative Folklore, with the electronics and tuning turned up to the max, but it too has received critical acclaim and was shortlisted for the Mercury Prize.

In many respects the albums speak to different moments of lockdown, with Charli XCX’s album released on 15 May 2020 and Swift’s on 27 July 2020. Both feature collaborations, Charli XCX with her fans and Swift with various musicians such as Dessner and Bon Iver. How I’m Feeling Now uses electronics, filters and audio techniques that replicate being quarantined in a digital age, whilst Swift's Folklore is minimalist. In the videos too there’s a marked difference in approach, in the case of Charli XCX, the vibe of the album is best captured in the trippy music video for ‘Claws’, with green screen digital backgrounds and kissing cyborgs that replicate the strangeness of isolation where human contact exists through the interface of our computer screens, connections forged through our Internet bubbles.

Although Swift's Folklore music videos have been produced in similarly restrictive circumstances, the style of a music video like 'Cardigan' (below) bears many of Swift's hallmarks including Easter Eggs to keep fans guessing and the solo musician battling unstoppable forces, in this case the stormy seas, in a scene reminiscent of 'Out of The Woods' (2014). The ethereal video to Folklore's first single, ‘Cardigan’ takes her Narnia-like through a piano lid into enchanted woodland and then out into the middle of the ocean before she returns again to a dimly lit room and the piano that remained by her side throughout, keeping her afloat and opening up new spaces for her to explore and create within.

Taylor Swift's Folklore and Charli XCX's How I'm Feeling Now are clearly quite different, musically and stylistically, but the timing of their release and the influence of COVID-19 on both artists makes it interesting to consider the two side-by-side, albeit in a relatively cursory way. Although both 'Claws' and 'Cardigan' can be read as speaking to the isolation of lockdown in their own fashion, neither falls into the category of addressing the pandemic directly, in the way other music released during lockdown has done, as I have mentioned above. Another category of music released during quarantine that has directly addressed the pandemic are those songs that have been released as part of a fundraising initiative, often with accompanying videos featuring images of life in lockdown. Examples include New Kids on the Block’s Houseparty a collaboration with Boyz II Men, Big Freedia, Naughty By Nature and Jordin Sparks with all net proceeds from the downloads and merchandise going to No Kid Hungry, Life In Quarantine by Death Cab For Cutie’s Benjamin Gibbard in benefit of Seattle-based non-profit Aurora Commons, an organisation that provides a safe space for people temporarily experiencing homelessness and Avril Lavigne’s We Are Warriors. The latter is a previously released song repurposed with a new video with all net proceeds from sales and streams going to Project HOPE’s ongoing COVID-19 relief efforts around the world including providing personal protective equipment (PPE) for frontline workers.

In the midst of a quiet world, the events in America following the death of George Floyd on 25 May 2020 saw an increasing number of artists directly responding to and addressing systemic racism and state sanctioned violence. In some cases, those artists were already producing music during the pandemic and I have discussed them above, such as Aluna. Following the death of George Floyd, Aluna prepared a Dance Renaissance session to raise funds for Breonna Taylor's gofundme and the Trans Justice Funding Project. Through new music, Black artists responded to the trauma and violence experienced by the Black community including Lil Baby’s The Bigger Picture and Beyoncé’s Black Parade, the latter released on Juneteenth. Performances like Dave’s Black at the 2020 BRIT Awards, Lauryn Hill’s Black Rage (2014) and Janelle Monae’s Hell You Talmbout (2015) were once again shared widely and remixes and new recordings of older songs like Sam Cooke’s A Change Is Gonna Come (1964) gave historic calls to action renewed purpose in the context of today’s movement.

In contrast to videos speaking to socially distant, isolated experience, the music videos accompanying tracks such as ‘The Bigger Picture’ and H.E.R’s I Can’t Breathe capture the power of collective action, the protests that followed in the wake of multiple instances of state-sanctioned violence. The movement has also reignited conversations about the significant legacy owed to Black culture within the music industry, the roots of musical genres like rock n roll and EDM, which originated from music produced within Black communities and, in the case of EDM and House, Black, queer community spaces.

In the midst of a quiet world, the events in America following the death of George Floyd on 25 May 2020 saw an increasing number of artists directly responding to and addressing systemic racism and state sanctioned violence. In some cases, those artists were already producing music during the pandemic and I have discussed them above, such as Aluna. Following the death of George Floyd, Aluna prepared a Dance Renaissance session to raise funds for Breonna Taylor's gofundme and the Trans Justice Funding Project. Through new music, Black artists responded to the trauma and violence experienced by the Black community including Lil Baby’s The Bigger Picture and Beyoncé’s Black Parade, the latter released on Juneteenth. Performances like Dave’s Black at the 2020 BRIT Awards, Lauryn Hill’s Black Rage (2014) and Janelle Monae’s Hell You Talmbout (2015) were once again shared widely and remixes and new recordings of older songs like Sam Cooke’s A Change Is Gonna Come (1964) gave historic calls to action renewed purpose in the context of today’s movement.

In contrast to videos speaking to socially distant, isolated experience, the music videos accompanying tracks such as ‘The Bigger Picture’ and H.E.R’s I Can’t Breathe capture the power of collective action, the protests that followed in the wake of multiple instances of state-sanctioned violence. The movement has also reignited conversations about the significant legacy owed to Black culture within the music industry, the roots of musical genres like rock n roll and EDM, which originated from music produced within Black communities and, in the case of EDM and House, Black, queer community spaces.

I have my own ‘Soundtrack For A Quarantine’ as I’m sure many of us who love music have developed over these months. During this period I found old songs took on a new resonance in a quiet world, I listened to musicians who were new to me for the first time and I found tremendous happiness in music livestreams, whether those organised by big record labels or smaller events, organised by friends in their homes and gardens. I’m sure that some of the songs that remind me of this particular time will find their way into my ‘Music Retrospectives’ series in due course, but in the meantime I’ll leave you with the one that I think has been my most listened to song. Released during lockdown, Orville Peck’s ‘Summertime’ was not inspired by his experiences of the pandemic, he has said in several interviews he penned the song long ago, but its themes of, in Peck’s own words, “biding your time and staying hopeful—even if it means missing something or someone” resonated during this particularly strange summer.