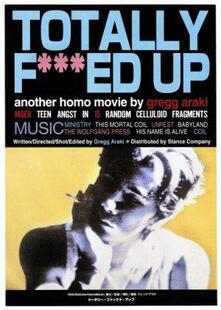

Totally F***ed Up (1993), directed by Gregg Araki, focuses on a group of queer friends. Andy (James Duval), a bisexual, filmmaker Steven (Gilbert Luna) and his boyfriend Deric (Lance May), Tommy (Roko Belic) who has an endless string of one night stands, and lesbian couple Michele (Susan Behshid) and Patricia (Jenee Gill). Totally F***ed Up employs the use of a home video footage to record interviews with the main characters. This gives the film an an initially fragmented feel as we are shown snippets of each character, without ever getting in-depth monologues or lengthy exposition.

Despite the fragmented nature of the film's beginnings, the filming technique serves to generate a sense of intimacy which makes the one-sided dialogue between the protagonists and the viewer appear conversational. The viewer is placed behind the camera in a fourth-wall-breaking strategy which is at once unreal and metatextual, positioning the viewer as filmmaker and part of the film's narrative.

Despite the fragmented nature of the film's beginnings, the filming technique serves to generate a sense of intimacy which makes the one-sided dialogue between the protagonists and the viewer appear conversational. The viewer is placed behind the camera in a fourth-wall-breaking strategy which is at once unreal and metatextual, positioning the viewer as filmmaker and part of the film's narrative.

As with many of Araki’s films, and something which is typical of the New Queer Cinema genre, the film’s focus (as opposed to a side-lined feature) is the queer protagonists, and it doesn’t shy away from addressing grittier topics. AIDS, homophobic bashing, drug use, suicide, infidelity, angst and alienation all get airtime as the story unfolds in a choppy series of interviews and slices of life. An ominous feeling pervades the film due to several references to violent and sadistic killings which have targeted gay men in the local community and the very real presence of death overshadows the film, contrasting sharply with Andy’s nihilism. The pieces of disjointed storytelling come together to form an essentially linear narrative, punctuated with unrelated sex scenes which appear on the screen momentarily in static-filled shots which add to the voyeuristic nature of the film.

Araki describes the film as "a rag-tag story of the...teen underground....a kinda cross between avant-garde experimental cinema and a queer John Hughes flick" and as with so many of his films, he hits the audience of a disaffected youth with a film which is utterly on point. The film doesn't shy away from the sexual experiences of the characters, but nor does the story dwell on the kind of angst over sex which is often seen in films with a young target audience. Instead, Araki offers queer youth a more gritty, realistic and representative portrayal of life, as opposed to pandering to the carefully sanitised romantic offerings from mainstream Hollywood.

The protagonists of Araki’s story are alienated by society but they have each other – the wide shots of empty car parks and dark, empty streets enforce the ‘us against the world’ group dynamic and contrast with the isolated interviews and moments of character-centric storytelling which sees the protagonists trying to forge their own paths as they deal with their own separate and distinct issues.

The film is punctuated with choppy excerpts of unrelated material, and it veers off course in places. There are conversations which allude to plot points that are never fully developed, and as the story loses focus this is reflected literally in filming techniques that make the picture quality less polished and crisp. However, these techniques reflect the lived reality of queer, teen experience, who by the nature of their queer identity already exist in a way that resists heteronormative linearity. The discordant narrative structure and cinematic techniques add to the authenticity of the film as the snippets slowly give way to narrative logic as the story develops and melds into a cohesive whole.

There’s a sense of futility and hopelessness at the film’s conclusion, yet the film is all the more powerful for it. It doesn’t deliver a happy ever after, but it also doesn’t make any false promises and nor does it treat its subject matter with condescension. It contains moments of irreverent humour and the relationships between the protagonists are – for the most part – warm and essential.

In making this film, Araki said his primary driver was "...to portray a way of life, a sub-culture which is totally ignored by both the mainstream and the conventional gay media – to represent the unrepresented. I would venture to say that queer teenagers – with all their loveable confusions and complexities – have never before been depicted as they are in this movie."

With Totally F***ked Up, Araki has succeeded in desire to represent the unrepresented, and to give a voice to the queer youth of the time.

Would recommend.

Araki describes the film as "a rag-tag story of the...teen underground....a kinda cross between avant-garde experimental cinema and a queer John Hughes flick" and as with so many of his films, he hits the audience of a disaffected youth with a film which is utterly on point. The film doesn't shy away from the sexual experiences of the characters, but nor does the story dwell on the kind of angst over sex which is often seen in films with a young target audience. Instead, Araki offers queer youth a more gritty, realistic and representative portrayal of life, as opposed to pandering to the carefully sanitised romantic offerings from mainstream Hollywood.

The protagonists of Araki’s story are alienated by society but they have each other – the wide shots of empty car parks and dark, empty streets enforce the ‘us against the world’ group dynamic and contrast with the isolated interviews and moments of character-centric storytelling which sees the protagonists trying to forge their own paths as they deal with their own separate and distinct issues.

The film is punctuated with choppy excerpts of unrelated material, and it veers off course in places. There are conversations which allude to plot points that are never fully developed, and as the story loses focus this is reflected literally in filming techniques that make the picture quality less polished and crisp. However, these techniques reflect the lived reality of queer, teen experience, who by the nature of their queer identity already exist in a way that resists heteronormative linearity. The discordant narrative structure and cinematic techniques add to the authenticity of the film as the snippets slowly give way to narrative logic as the story develops and melds into a cohesive whole.

There’s a sense of futility and hopelessness at the film’s conclusion, yet the film is all the more powerful for it. It doesn’t deliver a happy ever after, but it also doesn’t make any false promises and nor does it treat its subject matter with condescension. It contains moments of irreverent humour and the relationships between the protagonists are – for the most part – warm and essential.

In making this film, Araki said his primary driver was "...to portray a way of life, a sub-culture which is totally ignored by both the mainstream and the conventional gay media – to represent the unrepresented. I would venture to say that queer teenagers – with all their loveable confusions and complexities – have never before been depicted as they are in this movie."

With Totally F***ked Up, Araki has succeeded in desire to represent the unrepresented, and to give a voice to the queer youth of the time.

Would recommend.